Is a Universal Sign for Danger Possible?

Neonates & Nuclear Waste • 9 min read

Optimized for desktop, Last updated: 22 Nov 2021

1 Minute Summary

There are 2 general consensus on the topic of nuclear waste management:

-

Some believe that modern waste management and disposal techniques are sufficient to handle nuclear waste's potential 1,000,000 year lifespan.

-

Others believe that these modern methods are not enough to guarantee the safety of humanity in the far future for a variety of compelling reasons.

As a non-scientist, I have no say in the debate. But I am fascinated with the idea that due to ever-shifting changes in language, politics, and culture, humans in the far future wouldn't recognize or be able to read warnings of nuclear danger.

So the question remains: How will we mark nuclear waste for future generations?

There have been attempts in the past of solving this problem, ranging from radioactive cats to a nuclear priesthood with exclusive knowledge of waste sites. All attempts thus far have compelling strengths. But because they also have their flaws, I wanted to think through this problem myself and offer my own solution.

I believe the best shot at ensuring future humans understand modern day warnings is to leverage the visual nature of the human form. A combination of hostile architecture and praxeological structures are a strong contender for teaching future humans the concept of danger in a particular location.

Ai

1 week

Solo

Introduction

As nuclear technologies continue to play an ever-increasing role in modern energy production and military advancements, international opinion remains divided regarding strategies of safe high-level nuclear waste disposal.

Currently, high-level nuclear waste is estimated to remain at dangerous levels anywhere from 10,000 to 1,000,000 years depending on the concentration and origin.

To anyone with an understanding of how drastically human languages, ideas, and cultures evolve over millennia, these astronomical figures raise the ultimate question:

How will we mark nuclear waste for future generations?

A Sense of Scale

Maximum nuclear waste lifespan

Minimum nuclear waste lifespan

Average human lifespan

The Problem

Consider the following.

It would be overly dismissive to consider the answer to this question as simple as erecting a few signs around the waste zone that boldly read "Keep Out". In fact, listing the warning in 10 of the world's most common languages and putting any number of hazard symbols would hardly dissuade future humans from entering a radioactive waste zone.

To begin to understand the complexity, it helps to understand how language changes catastrophically over time:

Déað oferswýðeð.

Did you understand that ^?

No big deal, it's Old English. But imagine if your survival depended on whether or not you could understand what it means. This is the reality of future humans when they find our modern warning signs.

The phrase is a short excerpt from Beowulf, that would have been commonly understood by English speakers less than 1,000 years ago.

It means “death overpowers”.

Written language is not the answer.

In the span of just several hundred years the English language has evolved to the point of it being unrecognizable—even alien— to modern speakers.

As a reminder, radioactive waste is a minimum 10,000 year problem that will outlast all forms of current language and culture. Written language, as it currently exists, is not capable of answering the problem of marking nuclear waste for humanity in the far future.

Note: I'm not a linguist or engineer. I'm a visual designer trying to offer new ways to fix problems.

Challenges

Inherent vs. Imposed Meaning

What do a stop sign, thumbs-up, and biohazard icon all have in common? They all have meaning imposed onto them and lack a universal, inherent meaning.

Out of context, they mean nothing, or could be easily misinterpreted depending on your language, culture, or upbringing.

The solution must appeal to virtually everyone on earth regardless of their education or culture.

A red octagon with arbitrary Latin characters in no way naturally implies a command to stop. Likewise, curling your fingers into your palm and sticking your thumb upwards to imply positivity is a cultural construct. The biohazard symbol has become fairly ubiquitous to imply biological danger, but even it was intentionally designed to be memorable over inherently meaningful.

Changing Connotation

Even skulls and skeletons, the classic symbols of death and danger, have seen their meanings evolve over time. Only a few hundred years ago they generally represented poison, pirates, and death. But recently they have been deemed acceptable, even cool, in clothing, sports, branding, and popular culture.

They no longer necessitate the idea of imminent danger, but skulls and skeletons could still imply a general idea of danger in the right context.

Poison or hot sauce? Sea piracy or touchdown?

Long Term Durability

Even if we could find the perfect, fool-proof solution to this problem, it would be useless if it didn't last long enough to fulfill its purpose.

Weather events, natural erosion and decomposition, and vandalism all pose a threat to the longevity (and therefore the effectiveness) of the solution.

Honorable Mentions

Atomic Priesthood

In the 1970’s, the Human Interference Task Force was assembled in 1981 by the US Department of Energy for the sole purpose of keeping humans out of nuclear waste sites and to assuage the public’s fears toward nuclear energy.

A solution from Thomas Sebeok, a semiotician, was to form a so-called “atomic priesthood”—an exclusive order of men and women bearing the knowledge of nuclear waste sites and hazards. This strategy relies on devoted members passing down information, perhaps in the form of rituals or traditions to safeguard knowledge.

However, as outlined prior, language itself evolves and ideas change. What might have one meaning in the year 2050 might evolve and mean something completely different in the year 44,000.

Furthermore, if the priesthood dies out completely, either by apostates or assassination, who will be left to educate the world of radioactive waste sites?

Genetic Engineering

Another proposal involved genetically-engineered cats.

The idea is that if we can maintain a large population of felines that react to the presence of radioactive energy by glowing, we can know if we are within range of hazardous waste. This coupled with the dissemination of the idea that glowing cats means danger would ideally cause people near them to move away to a safer location. Nursery rhymes and art could be great methods for introducing this sentiment.

While this is theoretically possible, I foresee people in the far future with a lack of context eventually concluding that glowing cats are the danger, not indicators of it, and just opting to kill the cats and ignorantly carry on with their lives in an irradiated landscape.

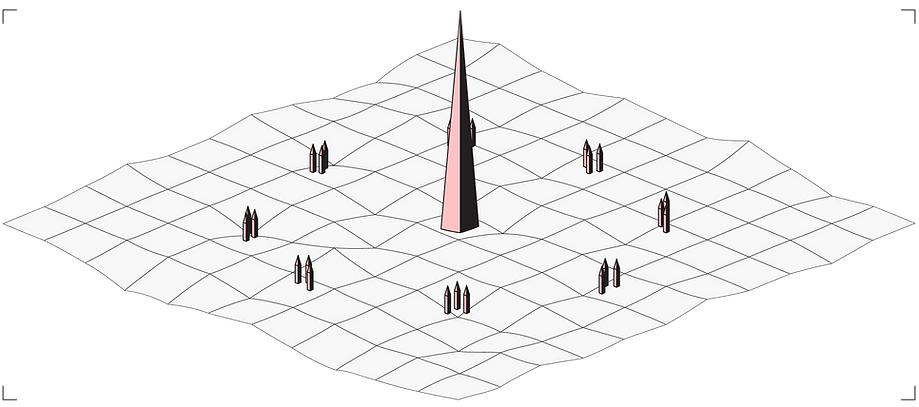

Hostile Architects

Another proposed solution was to alter the facade of waste sites to inspire fear in order to dissuade people from venturing too close. Oppressive spikes, needles, and obelisks bursting out of the earth would no doubt trigger some level of instinctual distrust.

The “hostile architecture” strategy relies heavily on the assumption that people will be terrified of the structures and not curious. Gregory Benford, a physicist and science fiction author and explains, “You want people to notice it but you don’t want people to go there. Those are always going to fight each other”.

It’s irresponsible to assume that the same species that explores the depths of the oceans and travels to space would be intimidated by ground structures.

Unmarked & Unspecified Locations

An intriguing proposition involves purposely not marking the waste repositories at all.

Combined with strategic waste locations, this method has some sensibility to it; people won’t be drawn to strange architecture or entrances if they simply don’t exist. A terrorist organization, for example, would have a much harder time using nuclear waste for the development of a weapon if the sites are simply forgotten and unmarked.

However with future technology and events uncertain, this strategy is perhaps wildly irresponsible. If better, future neutralization or utilization methods are developed for nuclear waste, future teams will be unable to easily locate them. An unmarked site may spell disaster for hapless drillers or developers in the future.

Praxeological Structures

The most compelling and promising avenue for development by far, in my opinion, is the advancement of the work of Florian Blanquer.

Blanquer theorizes that there is one universal symbol: an image of the human form. He proposed the implementation of “praxeological devices”—systems designed to teach viewers via practical, interactive methods. In them, participants are taught patterns and consequences via interacting with physical structures.

Blanquer proposed constructing the entrance of underground nuclear waste sites in such a way to teach people inside of them the dangers they face if they continue forward without completely sealing off the waste site.

One method to accomplish this is to line the floor of the hallway with human footprints that imply a sense of direction and encourage people to follow them with their own footsteps. As people progress down the hallway, they encounter a ladder leading vertically deeper into the structure, paired with a pictogram depicting a human figure safely holding onto it and climbing down the ladder.

The idea is to teach the person inside the structure to behave in a certain way by showing the result of certain pictured actions—walking in this direction leads to the ladder, safely using it leads deeper, etc. As this is repeated, the participant begins to see themselves symbolically in the human forms depicted in the pictograms and to trust them for safe instruction.

At the limits of safe distance from the waste site, navigation cues like footprints would stop. The pictographs at this point would depict someone foolishly going on and dying, perhaps falling to their death. Since the pictographs depict the results of actions, the participant will see that the result of moving forwards is death. Combined with the discontinuation of footprints, the participant will ideally decide to turn back.

This method of passing along abstract information is independent of prior education or knowledge, making it a strong contender. The only assumption required to understand is visual recognition of the human form and some sense of symbolism and causality.

Jean-Noël Dumont, head of the memory program at Andra, a French nuclear waste management agency, says, “Learning is important in the long term when you cannot just rely on transmission from generation to generation”. If human fascination is what lures people to these sites in the first place, that same fascination may likely help them learn from pictographs depicting danger.

Some New Ideas

My best idea.

Blanquer’s work forms the basis for my own solution of marking nuclear waste for future generations. I like the idea of using space and visual cues to teach people an abstract idea using the symbol of a human body. My idea is a simpler, less expensive method that may be more effective in regions that simply cannot afford to build underground structures.

My personal strategy combines the use of hostile architecture and praxeological elements to suggest the idea of “danger ahead”. This is accomplished through 2 main parts:

-

Three small obelisks, the middle of which has a pictograph pattern on its face

-

A fourth, larger obelisk with nuclear waste buried beneath it

+

The obelisks are arranged in a way where people cannot reach the central structure until they first pass by the 3 smaller structures. This essentially forces them to become a part of the installation and learn from the pictograph that is carved into the smaller obelisks.

Like in Blanquer’s pictographs, the idea is to establish that the human in the pictograph symbolizes the viewer.

It can be reasonably assumed that the viewer will make this connection because they share both the same geographical orientation to three obelisks and the same physical form as the pictured human. As a result, the viewer learns there is a direct relationship between the pictograph and reality—a relationship between the drawn human figure and themselves.

Therefore, the viewer should be inclined to stay away from the large obelisk, seeing via the pictograph that others near it have died, despite no bodies actually existing there. Think of it like an advanced “You are here” sticker that also implies “and you’ll die like the others if you venture onward”.

While skulls in and of themselves don’t necessarily imply threat of danger, the context of them pictured as impaled and arranged in a circular fashion are more likely to imply intentional hostility or danger in that area. In contrast, the human figure is alive where the viewer stands, reinforcing the idea that the location they’re currently in is safe.

User Flow Diagram

Some Considerations

The obelisks’ height helps ensure that despite erosion, damage, deposition, or flood, the pictograph will survive in some legible form. I’m no materials expert but perhaps an internal metal structure coated with a polymer composite would outlast a bare metal or stone structure.

In order to ensure that people will be warned from all directions, the collection of 3 obelisks with the pictograph should be repeated in a circular radius around the central waste repository obelisk.

Neonatal

So what do neonates have to do with nuclear waste?

The answer lies with my wife, a labor and delivery nurse. On a daily basis her department suffers from ineffective visual design—non-staff members ignoring warning signs and entering doors that sound alarms, leading to a lot of wasted time and annoyance.

Being a visual artist, she enlisted my help, requesting that I find a solution to the issue. It got me thinking there has to be a better, visual way to discourage people from doing a particular activity.

In this case, that activity is opening doors meant only for certain people. In my search for an answer, I happened upon a more pressing and threatening design problem: marking nuclear waste.

The rest is history.

Final Thoughts

I believe my solution is an interesting idea, albeit far from perfect and will require revisions and testing before its usefulness in real-world applications is validated.

Like any physical structure, this solution will not survive purposeful destruction. The strategy also hinges on correct interpretation of the pictograph which is not guaranteed. I admittedly was unable to visually describe the abstract concept of radioactivity, and instead settled on just danger. That avenue will require more research and design work.

If you have any constructive criticism or comments regarding the advancement or betterment of any of the proposed solutions here please contact me.

Sources

Dunn, Charles. “Multigenerational Warning Signs.” Stanford.edu, 17 Mar. 2011, large.stanford.edu/courses/2011/ph241/dunn2/.

Gordon, Helen. “How Do You Leave a Warning That Lasts as Long as Nuclear Waste?” Mosaic Science, 10 Sept. 2019, mosaicscience.com/story/how-do-you-leave-warning-lasts-long-nuclear-waste/.

Jamet, Marie, et al. “What Will a Nuclear Waste Warning Look like in 100,000 Years' Time?” Euronews, 26 Nov. 2018, www.euronews.com/2018/11/16/nuclear-waste-the-conundrum-over-how-to-warn-future-generations.

Kohlstedt, Kurt. “Beyond Biohazard: Why Danger Symbols Can't Last Forever.” 99% Invisible, 26 Jan. 2018, 99percentinvisible.org/article/beyond-biohazard-danger-symbols-cant-last-forever/.

Maurer, Robert J. “Danger Signs.” Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, 19 Mar. 2016, www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-traits-excellence/201603/danger-signs.

“Radioactive Waste Management.” Https://Www.world-Nuclear.org/, Feb. 2020, www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/nuclear-wastes/radioactive-waste-management.aspx.